Just as there are different types of healthy spinal curvatures, there are different types of spinal conditions that involve a loss of those healthy curves. Kyphosis is a term that refers to both the spine’s healthy front-to-back curvatures and when those curvatures become excessive and problematic.

When a person has an excessive front-to-back spinal curve of the upper back, this is commonly diagnosed as kyphosis and can give the body a rounded-forward appearance. While kyphosis can be treatable, results are never guaranteed and will depend on a number of important patient/condition characteristics.

Before we delve into the specifics of different types of kyphosis and address the question of whether or not it’s treatable, let’s start by defining the condition.

What is Kyphosis?

The spine is naturally curved because it makes it stronger, more flexible, and better able to evenly absorb and distribute mechanical stress that’s incurred during movement, but what happens if one or more of the spine’s healthy curves are replaced by unhealthy curves?

There are many different types of spinal conditions that involve a loss of its healthy and natural curves, such as scoliosis, lordosis, and kyphosis.

Scoliosis is a spinal condition characterized by an abnormal sideways curvature of the spine, while lordosis is an abnormal spinal curvature that curves too far inwards, towards the body’s center, often giving the body a swayback appearance.

Kyphosis, on the other hand, is an excessive outward curvature, with the curve bending away from the body’s center. The term hyperkyphosis refers specifically to the condition of abnormal kyphosis but is commonly used interchangeably with kyphosis by medical professionals.

The spine has three main sections: cervical (neck), thoracic (middle/upper back), and lumbar (lower back). The cervical and lumbar spine features lordotic curves as the spine bends inwards, while the thoracic spine features a kyphotic curve as the spine bends backward.

It’s important to understand that even in a healthy spine, there are natural curvature-degree ranges, kyphosis included, but when that range falls beyond a normal range, this is when it crosses into the spinal-condition category of hyperkyphosis.

A normal range of kyphotic curves falls between 20 and 40 degrees, and when a diagnosis of kyphosis is given, it commonly involves kyphosis curvatures that are 50+ degrees.

As kyphosis is defined as an over-pronounced backward spinal curvature, it commonly causes the appearance of an arch on the upper back, giving the upper body a rounded-forward appearance.

While abnormal kyphosis most commonly affects the thoracic spine, it can also affect the cervical spine.

There are two main types of abnormal kyphosis: postural and structural.

Postural Kyphosis

Postural kyphosis is the most prevalent type, and when it comes to addressing the question of whether or not it’s reversible, the answer is yes because this form is not structural.

When a spinal condition is structural, it means that the condition is caused by a structural abnormality within the spine itself.

In postural kyphosis, as the name suggests, causation is chronic poor posture, which can be somewhat easily corrected.

For example, with postural kyphosis, if a person were to lay flat on the floor and make an active effort to straighten their curve, so the length of the spine is in contact with the floor, the abnormal kyphosis can be corrected.

Postural kyphosis is commonly diagnosed in adolescence and is more likely to affect girls than boys.

The condition is commonly caused by poor posture, such as slouching and staring down at devices for extended periods of time, which can lead to what’s known as forward head posture.

Forward head posture develops when there is a shift forward in posture. If you think of a person sitting in a chair and looking down at their phone, the phone is rarely held up to eye level, and instead, the cervical spine is extended forward to look down, and this actually increases the weight of the head on the cervical and upper spine exponentially.

Treatment for Postural Kyphosis

The good news is that as postural kyphosis is not structural, it is highly treatable and can somewhat easily be reversed by addressing the bad postural and movement patterns that led to its development.

Commonly, treatment includes practicing good posture and utilizing condition-specific physical therapy exercises that encourage spinal extension and increase core strength so the muscles that surround the spine can optimally support and stabilize it.

Conversely, structural kyphosis is far more complex to treat, and whether or not it’s reversible depends on a number of important patient/condition variables.

Structural Kyphosis

As mentioned, a structural spinal condition means its causation is due to the presence of a structural abnormality within the spine itself, and while they can still be treatable, whether or not they are reversible will depend on a number of important factors.

Scheuermann’s kyphosis is the most common type of structural kyphosis and was named after the radiologist who first described the condition.

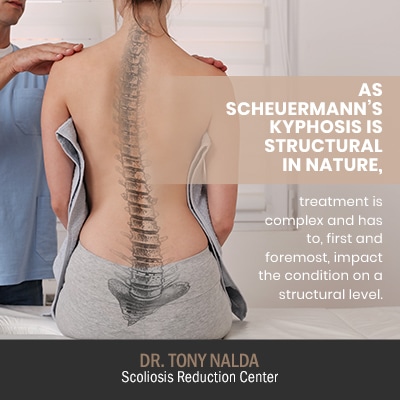

Unlike postural kyphosis, where a change in position can help correct the abnormal spinal curve, with Scheuermann’s kyphosis, no change in posture or position has the power to impact the condition on a structural level.

The vertebrae (bones of the spine) in a healthy spine are rectangular in shape; this allows them to be neatly stacked on top of one another (separated by intervertebral discs) in a neutral and healthy alignment.

In cases of Scheuermann’s kyphosis, one or more vertebrae are triangular in shape, and this causes the vertebrae to become wedged together and curve forward: impacting the biomechanics of the entire spine, impairing its ability to maintain its natural alignment and curvatures, and causing the forward-rounding of the thoracic spine.

Scheuermann’s is most commonly diagnosed during adolescence, and this form is more prevalent in boys than girls.

While every case is different and will produce its own unique set of symptoms, Scheuermann’s kyphosis can be painful, especially during long-standing, sitting, or activity periods.

While the kyphotic curves in postural kyphosis are flexible, Scheuermann’s kyphotic curves are rigid, which is why they are more complex to treat.

Treatment for Scheuermann’s Kyphosis

As Scheuermann’s kyphosis is structural in nature, treatment is complex and has to, first and foremost, impact the condition on a structural level.

This means that more work has to be done to change the structure of the spine itself and restore as much of the spine’s healthy curves as possible.

So the answer to the question, can you completely fix kyphosis, will depend on a number of factors including patient age, whether or not it’s structural, condition severity, and curvature flexibility.

Every case is different, which is why customizing treatment plans to address these specific and important variables is key to treatment success.

While no treatment results can ever be guaranteed, here at the Scoliosis Reduction Center®, I can offer effective and proactive treatment for kyphosis by impacting the condition on multiple levels.

I believe in a proactive, functional, conservative, and chiropractic-centered approach to treating kyphosis; this means that preserving the spine’s overall health and function is the linchpin of treatment.

Combining different treatment disciplines allows me to fully customize each and every treatment plan to address the specifics of the patients and their conditions.

For treating my kyphosis patients, I combine kyphosis-specific chiropractic care that works towards changing the structure of the spine itself, in-office therapy, custom-prescribed home exercises, and corrective bracing (more commonly used for younger patients).

Through chiropractic care, I work towards adjusting the most-tilted vertebrae of the curvature back into a healthier alignment with the rest of the spine. My in-office therapy and custom-prescribed home exercises encourage spinal extension while increasing core strength so the spine is better supported and stabilized by its surrounding muscles.

Depending on condition severity, the age of the patient (whether or not age-related spinal deterioration is a factor), and how much flexibility is left in the spine, some cases can be reversible, while with some severe forms, and/or with older patients, it’s more accurate to say the abnormal kyphosis can be reduced, rather than fully reversed.

When considering kyphosis treatment, one may wonder whether kyphosis is reversible or treatable. The answer largely depends on factors such as the severity of the condition. In some cases, kyphosis exercises and the use of a kyphosis back brace may help improve posture and alleviate symptoms, particularly in cases of mild to moderate kyphotic curves.

Kyphosis treatment aims to address the curvature of the spine, but whether dowager’s hump, a characteristic manifestation of kyphosis, is reversible or treatable depends on various factors and the severity of the condition.

However, more severe instances might necessitate kyphosis surgery, which can provide a more significant correction to reverse thoracic kyphosis and enhance spinal alignment. It’s important to consult with a healthcare professional to determine the most suitable treatment approach based on the individual’s specific condition.

Conclusion

Kyphosis, a condition characterized by an excessive forward rounding of the upper back, can be managed through various approaches, but it’s essential to understand that complete reversal may not always be achievable. To address thoracic kyphosis, a healthcare provider may recommend kyphosis exercises designed to improve posture and strengthen the back muscles, which can be a helpful part of treatment.

The use of a kyphosis back brace may also assist in maintaining proper spinal alignment. While these treatments can help alleviate discomfort and prevent further progression of the kyphotic curve, it’s essential to consult with a healthcare professional for personalized guidance and a thorough understanding of what is kyphosis and the available treatment options.

Kyphosis, whether congenital or acquired, can be treated through a variety of kyphosis therapies and treatments. In adults, the approach to kyphosis treatment typically includes physical therapy and exercises designed to enhance posture and strengthen the back muscles. In severe cases of kyphosis, spinal fusion surgery may be recommended to correct the curvature and provide long-term relief.

While these treatments can help improve posture and alleviate discomfort, it’s important to note that complete reversibility may not always be achievable, especially in cases related to structural issues within the spinal cord. Nevertheless, early diagnosis and appropriate kyphosis nursing interventions are crucial for managing the condition effectively and ensuring the best possible outcomes.

When it comes to spinal conditions, like kyphosis, that involve a loss of the spine’s healthy curves, most cases are highly treatable.

However, it’s important to understand that treatment results can never be guaranteed, and treatability also depends on a number of important patient/condition characteristics such as patient age, condition type (postural or structural), condition severity, and curvature flexibility.

In cases of postural kyphosis, they are not only highly treatable but can also be completely reversed if the bad postural and movement habits that caused its development are remedied. Most commonly, this involves correcting bad posture habits and integrating spinal-extension and core-strengthening exercises into a routine.

When it comes to structural kyphosis, such as Scheuermann’s, as the condition is structural, it can be far more complex to treat. Treatment success will depend on a number of important factors, including condition severity, patient age, and curvature flexibility.

With cases of Scheuermann’s, proactive efforts have to be made to impact the condition on a structural level, which can involve condition-specific chiropractic adjustments and the use of specific exercises to increase spinal and core strength, so the spine is optimally supported and stabilized, and particularly with younger patients, corrective bracing can also play a role in treatment.

If you, or someone you care about, are concerned about spinal health and function, don’t hesitate to reach out to me here at the Scoliosis Reduction Center® for guidance, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment.