Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the condition’s most common form. It affects adolescents between the ages of 10 and 18 and makes up for 80 percent of known diagnosed scoliosis cases; however, despite its prevalence and the amount of study done on the subject, we still don’t fully understand its etiology. Keep reading for further understanding of the condition’s symptoms and treatment options.

Idiopathic scoliosis is a spinal condition marked by an abnormal sideways spinal curvature, with rotation, that has no single known cause, hence the ‘idiopathic’ classification. Symptoms range widely based largely on condition severity, and patients have two main treatment approaches to choose between.

While idiopathic scoliosis is more common in children and adolescents, adults can develop the condition too. Before we go into how idiopathic scoliosis affects adults, let’s start with the defining characteristics of the most condition’s common form: adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

While there are many different types of scoliosis that can develop, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the condition’s most common form.

AIS patients make up 80 percent of known scoliosis cases in the United States, diagnosed between the ages of 10 and 18. The other 20 percent are cases with known causes such as congenital, neuromuscular, degenerative, and traumatic.

While idiopathic scoliosis can develop in toddlers and children as well, it’s far more common in adolescents.

Despite the fact that scoliosis has been around for hundreds of years and the amount of research and studies done on the subject of AIS, the medical community has yet to isolate one single known cause that accounts for the development of idiopathic scoliosis.

The general consensus amongst scoliosis experts is that AIS is ‘multifactorial’, meaning it’s likely caused by multiple factors, or the way certain factors combine, and these factors can vary from person to person.

In addition to the condition’s idiopathic designation, another of its defining characteristics is that it’s progressive, meaning its very nature is to worsen over time, which is also why it’s incurable.

While all forms of scoliosis are progressive, when it comes to idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents, this age group is at risk for rapid-phase progression, and this characteristic becomes one of the guiding forces behind treatment.

Progression and Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

One of the big challenges of treating scoliosis is progression. The main trigger for progression is growth, which is why the condition is so prevalent amongst adolescents: this age group is entering into, or is in, a significant phase of growth and development, marked by rapid and unpredictable growth spurts.

While we understand the progressive nature of AIS and can work towards controlling it, no one can accurately predict an individual’s rate of progression.

We also know that females who develop scoliosis are approximately eight times more likely to experience progression than males; this is generally understood as the result of earlier growth and development, characteristic of female adolescents.

Once a person reaches skeletal maturity, meaning they have stopped growing, progression still occurs, but generally at a slower rate. There is a growth indicator that’s visible via X-ray to help predict progression known as the ‘Risser sign’.

A patient’s Risser sign refers to their level of pelvic calcification. It’s measured on a scale of 0 to 5, with 5 meaning skeletal maturity. Generally, the higher a patient’s Risser score, the closer they are to reaching skeletal maturity, the less growth they have yet to go through, and the less likely rapid-phase progression will be.

In addition, a patient’s curvature pattern can also help us gauge a patient’s ‘likeliest’ rate of progression as some curvature patterns are more likely to progress. Curvatures that develop along the thoracic spine (middle and upper back) are the most common and the most likely to progress.

So as you can see, while there is no quick-and-easy method for definitively determining a patient’s rate of progression, there are patient and condition characteristics that help us predict the level of progression we are most likely dealing with.

Now that we have touched on the most common form of idiopathic scoliosis and explored its progressive nature, let’s take a look at some of the telltale signs and symptoms of AIS, as this awareness can help lead to early detection.

Symptoms of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

I mentioned that the unpredictable nature of progression was a challenge to treating scoliosis; another challenge behind AIS is early detection.

While it might seem like an abnormally-curved spine and related changes to the body would be noticeable, that’s not always the case.

‘Early detection’ means diagnosing the condition in its early days, before it progresses significantly. This is important not only because as a progressive condition, we want to catch the condition as early as possible so we can start treatment, but also so we can spare our patients the hardships of reaching the higher stages of progression.

Smaller curvatures are less complex to treat, and the body has not yet had the time to adjust to the spine’s abnormal curvature. While early detection doesn’t guarantee successful treatment outcome (nothing and no one can do that), it does substantially increase chances of treatment success.

Condition severity is a big determining factor when it comes to a condition’s symptoms. Generally, the more severe a condition, the more noticeable the symptoms are going to be.

Cobb Angle

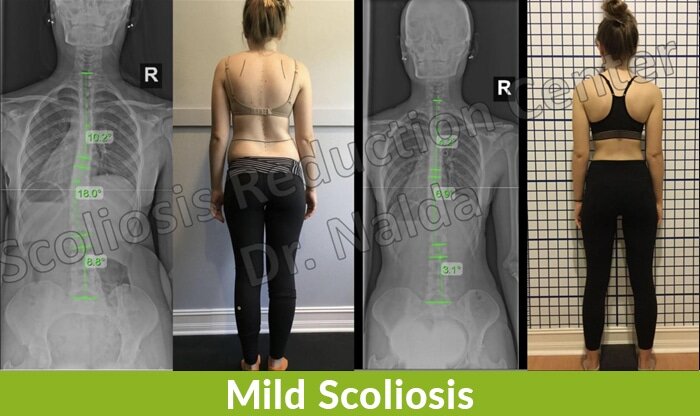

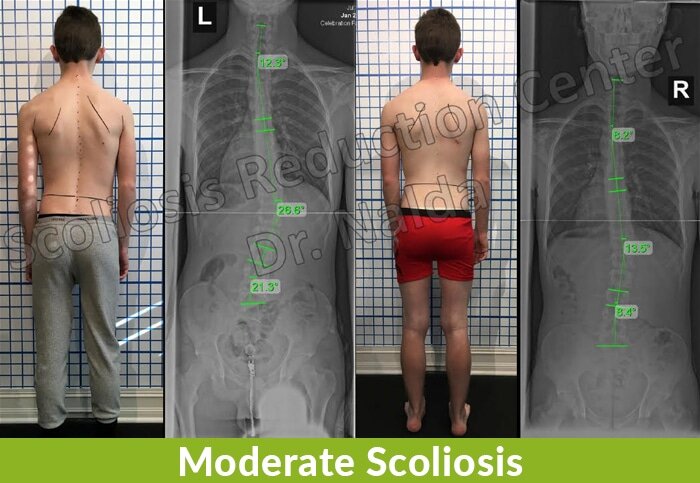

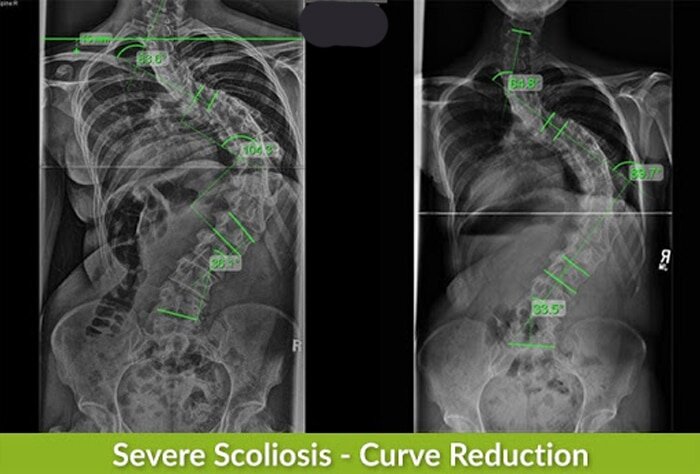

Condition severity is determined based on the patient’s Cobb angle. Cobb angle is a measurement obtained via X-ray that expresses how far out of a natural alignment a scoliotic spine is.

A patient’s Cobb angle is measured by drawing intersecting lines from the tops and bottoms of the most-tilted vertebrae (bones of the spine) of the curvature, and the resulting angle is measured in degrees.

The higher the angle, the more out of alignment the spine is, the more severe the condition is, and the more likely it is that related symptoms will be noticeable. Based on the patient’s Cobb angle, the condition is placed on its severity scale of mild, moderate, severe, or very severe.

- Mild scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 10 and 25 degrees

- Moderate scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 25 and 40 degrees

- Severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 40+ degrees

- Very-severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 80+ degrees

Now, just to give you an idea of the wide range of curvature sizes that can develop, the largest I’ve seen was 150 degrees, so from 10 (the minimum Cobb angle necessary for a scoliosis diagnosis) all the way up to the 100’s, you can see how much of a range there can be.

In cases of mild scoliosis, the condition’s signs and symptoms can be very subtle and difficult for anyone, other than an expert who is trained in what to look for, to notice; this is, again, why early detection isn’t always easy to achieve.

Generally, the most overt signs of scoliosis in adolescents involve the body’s posture, symmetry, and the appearance of the hips, shoulder blades, and the back.

In addition, changes to the way an adolescent’s clothing fits can also be a sign. If shirt necklines seem to start favoring one side more than the other, or if shirt cuffs and pant legs seem uneven, this could be an indicator of scoliosis.

Additional signs and symptoms related to posture and symmetry include:

- Ribs that protrude more on one side

- Unevenness during motion

- Arms that are held tightly to the sides while walking

- One hip that is more prominent than the other

- A head that appears uncentered over the body

- One shoulder blade sitting higher than the other or protruding more prominently

- Legs and arms that seem to hang at different lengths

- Clothing that used to fit but seems ill-fitting

- An eye line that appears tilted

- Changes to gait

- Spinal curvature that is visible to the naked eye

The aforementioned signs are the most obvious visual symptoms of the condition, and in addition, idiopathic scoliosis symptoms can include impairment in balance and proprioception(ability of the body to recognize its position with no visual cues), and excess tiredness and fatigue.

While scoliosis is most commonly diagnosed in adolescence, adults can develop it too, so let’s move on to discussing idiopathic scoliosis in adults.

Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adults

When it comes to idiopathic scoliosis in adulthood, this is the most common form affecting adults; however, these cases don’t develop fresh in adulthood, and rather are continuations of AIS that have progressed into maturity.

As mentioned, symptoms and signs of mild AIS aren’t always obvious, noticeable, and most often don’t produce functional deficits.

In addition, as AIS isn’t painful, this makes it even more difficult to know that something is wrong in the body. Once these adolescents reach skeletal maturity, this is often when the condition becomes painful, which is the number-one reason adults come to see me.

In patients who are still growing, the spine is constantly experiencing a lengthening motion, and this counteracts the compressive force of the curvature, but once that growth factor is removed and skeletal maturity has been reached, adults can experience varying levels of pain in the back, neck, and pain that radiates into the legs and feet.

Unfortunately, had these patients received a diagnosis and treatment in adolescence, they would be in much better shape than where they are by the time they see me and their condition has progressed.

When it comes to progression in adult idiopathic scoliosis, there are varying rates, and can generally be measured anywhere from half a degree to two degrees a year. Progression can also increase significantly after the age of 50, due to the degenerative effects of aging on the spine.

Adults who come to see me for a diagnosis are coming in because they are experiencing noticeable symptoms.

Symptoms of Idiopathic Scoliosis in Adults

Again, when it comes to scoliosis, symptoms range based on a number of factors such as patient age and condition severity.

Some common symptoms include a pronounced asymmetrical lean to one side, an uneven shoulder height, or the presence of a rib arch. It’s quite common for adults to notice multiple symptoms, and the postural changes are often more noticeable when in a forward-bend position.

The biggest difference in condition experience between idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents versus idiopathic scoliosis in adults is pain. In adults, back and related pain can be intense.

As adults are no longer growing, they are vulnerable to the pressure caused by the abnormal spinal curvature. Once an adult has stopped growing, their spines have settled due to gravity, making them vulnerable to compression.

When elements of the spine are compressed, this puts excess pressure on the nerves, known to be the cause of radiating pain, and the entire spinal cord, and this only increases as scoliosis curves develop and progress in severity.

In addition, in severe cases of adult scoliosis, the adverse pressure and spinal tension can lead to impairments in coordination and the ability to use the limbs. This can make it difficult to walk or take part in certain physical activities.

Fortunately, these symptoms are less common, but they should be included as an example of what progression left untreated can lead to in severe cases of idiopathic scoliosis in adults.

Now that we have touched on the main characteristics of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents and adults, let’s move on to the all-important topic of treatment.

Treatment for Idiopathic Scoliosis

One of the biggest decisions to be made following a scoliosis diagnosis is how to treat it. Different treatment approaches offer patients different outcomes, so it’s important to really understand the differences; patients and their families need to make a fully-informed choice as the outcome can have far-reaching consequences.

When it comes to treatment time for scoliosis patients, they have two main approaches to choose between: functional and traditional.

Functional Treatment Approach

Here at the Scoliosis Reduction Center®, I am extremely proud of what we have built and the level of care we can offer our patients.

Our approach is functional and proactive. I regard the health and function of the spine as the highest priority and feel that preserving these things means preserving a patient’s quality of life.

While curvature reduction is also our goal, the way we get there is important. While another approach might be able to offer patients a more extreme curvature reduction, say through spinal-fusion surgery, when that treatment process costs patients their mobility, impairing the spine’s overall function, that price is high and unnecessary.

My approach is integrative and combines different treatment disciplines because I feel the nature of idiopathic scoliosis necessitates this; as it’s considered to be multifactorial, it makes sense that a condition caused by multiple variables would benefit from an approach that draws from multiple forms of treatment.

Our functional approach here at the Center is customized to suit every patient and their condition, and the disciplines we combine are all scoliosis-specific: chiropractic care, in-office therapy, custom-prescribed home exercises, and specialized corrective bracing.

We work closely with our patients and their families to, first and foremost, impact the condition on a structural level by reducing the abnormal spinal curvature as much as possible. We also work towards improving core strength so the muscles located closely to the spine are better able to support and stabilize it.

Our specialized corrective ScoliBrace is vastly superior to other bracing options on the market in terms of design and preserving the spine’s function. While other traditional braces have slowing/stopping progression as their end-goal, the modern ScoliBrace has correction as the driving force behind its design.

Traditional Treatment Approach

The traditional approach has been around for almost as long as the condition itself, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best option by any means.

The traditional approach to scoliosis treatment is far more passive than a functional approach. We know that scoliosis is progressive, but those following the traditional path of scoliosis treatment are often told that while the condition is mild, there is little recourse other than watching and waiting to see if, and how fast, a condition will progress.

The problem I have with watching and waiting is that it’s wasting valuable treatment time and leaving a small and, potentially treatable, curvature to progress unimpeded. In addition to watching and waiting, rather than starting treatment right away, the traditional approach favors the use of traditional braces such as the Boston or Milwaukee brace.

As mentioned, these braces represent a different end-goal, and patients don’t benefit from what we have learned about bracing and scoliosis over the years, as they do with the ScoliBrace.

After watching and waiting, and likely being told to wear a Boston brace to control progression, what can happen is because proactive efforts weren’t made to impact the condition structurally early on, the patient’s curvature progresses to the point where they pass the surgical-level threshold; in this way, patients are funnelled towards spinal-fusion surgery.

Spinal-Fusion Surgery

While there have been advancements in the hardware used for spinal fusion, the underlying goal and process has remained relatively unchanged over the years.

The most-tilted vertebrae of the curvature are fused together to form one solid bone, and rods are attached to the spine to keep it in place while it heals. The end-goal is not correction, but to stop the curvature from getting worse.

As the spine is fused, that lack of movement can help stop progression, but it is never guaranteed to do so, and as there is a permanent lack of flexibility in that section of the spine, this can limit a patient’s range of movement significantly.

In addition, many patients are also disappointed to find that their pain levels increase post-surgery due to the stiffness of the fusion site and its effect on the spine’s surrounding muscles.

Just as any surgical procedure comes with risks, spinal fusion is no exception. It’s a long, costly, and invasive procedure that carries some heavy potential side effects and risk of complications, not to mention a lack of long-term data on the effects of spinal fusion 20, 30, and 40 years down the road.

Also, the results of spinal fusion are permanent. There is no un-fusing a fused spine, and the only recourse for an unsuccessful spinal fusion is more surgery, which of course comes with additional risks.

In the end, a patient has to decide what type of treatment outcome they are looking for. While spinal fusion can be successful in terms of straightening a crooked spine, a smaller curve reduction achieved through more natural and functional means can offer patients less pain, more flexibility, and a better range of motion and quality of life.

Conclusion

It can be hard to look at a patient, give them an idiopathic scoliosis diagnosis, and then have to explain that there is no known single cause. Being diagnosed with a progressive and incurable spinal condition can make patients feel as though they have lost control over their bodies and lives, and that’s a challenge for anyone to deal with.

What I like to point out is that while we don’t fully understand the etiology of idiopathic scoliosis, we most certainly understand its symptoms and how to treat it, and knowing the cause would not necessarily change the treatment design and/or outcome.

I also like to point out that as they have recognized the symptoms and signs of the condition and received a diagnosis, the benefits of early detection are available to them; however, these benefits, in terms of treatment efficacy, are only available to those who are choosing a proactive approach that believes in starting treatment as close to the time of diagnosis as possible.

From there, we want our patients to move forward with proactive functional treatment in as positive a light as possible. Those who choose a more traditional approach are walking a more-passive path that tends to funnel people towards spinal-fusion surgery, and that is something I think patients should consider only as a lost option once other less-invasive forms of treatment have been explored.

Here at the Scoliosis Reduction Center®, we are working towards changing the narrative that surrounds the condition, one positive treatment outcome at a time.