While screening and assessment can’t help us prevent the onset of scoliosis, what it can do is help us reach a diagnosis early on in the condition’s progressive line. This is highly beneficial in terms of treatment efficacy because it means treating an abnormal spinal curvature before it has a chance to progress in severity.

With scoliosis testing, screening for scoliosis, and assessment, the goal is to diagnose and assess a condition thoroughly so we have the information needed to design a customized treatment plan. There are also different treatment approaches, with some recommending observation as the next step following a diagnosis, and others favoring a more proactive response.

Before we start exploring the basics of scoliosis testing, screening, and assessment, let’s first talk about why conducting scoliosis screening can be an important part of reaching a diagnosis.

Understanding Scoliosis

Scoliosis is a medical condition characterized by an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine. It can affect individuals of all ages, but it is most commonly diagnosed in children and adolescents. The condition can arise from various factors, including genetics, neuromuscular conditions, and congenital abnormalities. In some cases, the cause of scoliosis remains unknown, and this is referred to as idiopathic scoliosis.

There are several types of scoliosis, each with distinct characteristics:

- Congenital Scoliosis: This type is present at birth and results from a congenital abnormality of the spine. It occurs due to malformations in the vertebrae that develop during fetal growth.

- Neuromuscular Scoliosis: This type is associated with neuromuscular conditions such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy. These conditions affect the muscles and nerves that support the spine, leading to curvature.

- Idiopathic Scoliosis: The most common type, idiopathic scoliosis, is characterized by an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine with no known cause. It accounts for approximately 80% of scoliosis cases.

Scoliosis can manifest through a range of symptoms, including:

- Uneven shoulders or hips

- A visible curvature of the spine

- Back pain

- Difficulty breathing

Early detection of scoliosis is crucial to prevent the curvature from worsening and to reduce the risk of long-term complications. Recognizing the signs and seeking prompt medical evaluation can lead to more effective treatment outcomes.

Scoliosis and Progression

As prevalent as scoliosis is, many people have a basic understanding of what it is: a spinal condition marked by an abnormal sideways curvature. What a lot of people don’t realize is that it’s a progressive condition, and understanding the nature of progressive conditions is an important part of understanding scoliosis as a whole. Any spinal curve greater than 10 degrees is considered scoliosis.

When a person develops scoliosis, their spine has an abnormal sideways curvature that includes rotation; this means that their spine has lost one or more of its healthy curves.

When scoliosis is present, this disrupts the spine’s biomechanics as the main healthy curvatures that are characteristic of the three main spinal sections (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar) are lost.

The spine’s natural curves help us to maintain straight and upright posture, evenly distribute the stress that’s incurred during movement, and help give the spine its strength and flexibility.

When those healthy curves are lost, the body responds by putting in bad curves. As a progressive condition, scoliosis is going to get worse over time, meaning the abnormal spinal curvature will get larger, and related symptoms, such as postural changes and pain, will likely increase as well.

Now, let’s take a minute to specifically address progression in the condition’s most common form: adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis and Progression

The age group that’s most commonly diagnosed with scoliosis is between the ages of 10 and 18; this form is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and accounts for 80 percent of known diagnosed cases.

The ‘idiopathic’ designation means there is no single known cause. Experts generally agree that AIS is, instead, multifactorial: caused by multiple factors that can vary from one person to the next.

So while there is still much about the most common form of scoliosis that we don’t fully understand, one thing we do know and understand is how beneficial it is to catch the condition early on so we can start treatment.

School screening plays a crucial role in the early detection of scoliosis, particularly through methods like the Adam’s forward bend test, which helps identify potential cases among children during growth spurts.

We also know that growth and development is the big trigger for progression. When we are talking about adolescents and teenagers entering into and moving through the puberty stage, marked by rapid and unpredictable growth spurts, this is the big challenge to treatment: staying ahead of the condition’s nature to progress with growth.

In addition, although we know what triggers progression, there is no way to predict precisely at what rate a patient’s condition is going to progress. This is why screening and assessment is so important because every effort has to be made proactively control progression so the later stages of severity can be avoided, and the only way to achieve that is through active treatment.

Diagnosing AIS can be challenging because it’s typically not a painful condition, and in mild forms, it rarely produces functional deficits. In addition, symptoms like postural changes can be very subtle and only noticeable to an expert who knows exactly what to look for.

For many, AIS isn’t painful because as we’re talking about adolescent and teenage patients who have not yet reached skeletal maturity, their spines are constantly growing, and this counteracts the compressive force of the curvature, known as the source of pain in adult scoliosis.

While the condition is far more commonly diagnosed in adolescence, adults can develop it too, so let’s move on to the role of progression in adult scoliosis.

Adult Scoliosis and Progression

When it comes to adults with scoliosis, there are two main forms: idiopathic scoliosis and degenerative scoliosis.

The former are cases of AIS that remained undiagnosed until adulthood. It might seem hard to imagine that a spinal condition could go unnoticed for so long, but as we will be returning to later, a condition’s degree of severity plays a big role in how subtle or overt its symptoms are. School screenings can detect scoliosis early, which is crucial for timely intervention.

The latter, degenerative scoliosis, presents in adults over the age of 40 and develops due to the cumulative effects of years of wear and tear and lifestyle choices on the spine’s health, most commonly the intervertebral discs.

Now, once skeletal maturity has been reached, the main trigger for progression (growth) has been removed, but that doesn’t mean that adult scoliosis won’t progress; it just means that it is more likely to progress at a slower rate.

So in the more common form of adult scoliosis, idiopathic scoliosis, you can see how beneficial it would have been to have caught the condition when it first developed in adolescence.

When most adults with idiopathic scoliosis come in to see me, it’s pain that brings them in and has alerted them to the fact that something is wrong. Had they been screened, tested, and assessed during adolescence when they first developed the condition, reached a diagnosis and seeking treatment, they would have been in far better shape; instead, after leaving it to progress over the years unimpeded, the curvature will be more severe and complex to treat.

In exploring the main forms of scoliosis in adolescents and adults, we have a better understanding of how the condition progresses and why reaching an early diagnosis can lead to better treatment results.

Now let’s move on to the process from screening and testing to diagnosis, assessment, and treatment.

Scoliosis Screening

In the medical world, when we say ‘screening’, we mean checking a person for indicators of a condition.

One such method is the Adam’s forward bend test, which is used to detect scoliosis by assessing spinal asymmetry and other indicators. Having one or two indicators doesn’t automatically mean a person has the condition, but it does signal a need for further testing to reach definitive answers.

There was a time when regular scoliosis screening was offered in schools across the country, but that has since changed due to cost and reliability concerns. The forward bending test plays a significant role in school screenings, often combined with other tests to improve early detection. The policies regarding school scoliosis-screening programs now differ from state to state, with some offering it and others not.

While there has been some uncertainty over the effectiveness of school scoliosis-screening programs and its effect on curve magnitude at time of presentation, we do know that, on an individual basis, scoliosis screening and testing can help lead to early diagnosis and treatment.

In fact, a group in charge of compiling research-based guidelines for the treatment of medical conditions, The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, states that the choice to screen for scoliosis should fall into the hands of the parents and/or caregivers, a patient’s doctor, and/or the medical office in charge of providing the patient’s health services.

As scoliosis commonly first appears with the first big growth spurt, it’s suggested that scoliosis screening should be conducted prior to when adolescents are likely to have that first big growth spurt.

As scoliosis is more common in girls and they are at a higher risk of progression than boys, it’s recommended that girls be screened twice at the ages of 10 and 12, and boys should be getting screened once between the ages 13 and 15.

This is, in part, why I wrote Scoliosis Hope: to give parents and caregivers all the information they need so they can take the screening reigns themselves and be more proactive and in control of their children’s health.

The first step to being able to spot a condition early on is knowing the kinds of subtle signs to look for.

Scoliosis Detection and Diagnosis

Detecting scoliosis typically begins with a physical examination, which includes a visual inspection of the spine and a forward bend test. The forward bend test, also known as the Adam’s forward bend test, is a simple yet effective method. During this test, the child bends forward at the waist while the examiner looks for any signs of spinal curvature.

In addition to the physical examination, imaging tests such as X-rays or MRI scans are often used to confirm the diagnosis of scoliosis and to measure the degree of curvature. These imaging tests provide detailed views of the spine, allowing healthcare providers to assess the severity of the condition accurately.

The Scoliosis Research Society recommends that children be screened for scoliosis at least twice, once at age 10 and again at age 12 or 13. Children with a family history of scoliosis or those at risk due to a neuromuscular condition should be screened more frequently. Early detection through regular screening can lead to timely intervention and better management of the condition.

Early Scoliosis Signs for Parents and/or Caregivers to Watch For

As mentioned, in the condition’s most common form, AIS, spotting the condition early on can be particularly difficult, and a main factor in just how subtle or obvious signs are is condition severity; this leads us into what’s known as ‘Cobb angle’, but we’ll return to that later.

For now, let’s spend some time informing parents and/or caregivers what some early signs of scoliosis are and how to spot them.

Postural Changes to Watch For

While there is no one-size-fits-all response to scoliosis as each and every patient will have their own unique condition characteristics and experienced symptoms, there are some telltale signs to look for.

The most obvious signs of scoliosis in adolescents are related to posture, symmetry, the appearance of the shoulders, shoulder blades, and back:

- Head appearing not centered over the body

- Uneven shoulders

- One shoulder blade protruding more on one side than the other

- Ribs protruding more on one side than the other

- One hip sitting higher than the other

- Legs and arms appear to be different lengths

- A spinal curvature that’s visible to the naked eye

You might start to notice that clothing seems to fit your child differently. It might seem to hang unevenly: necklines can look crooked, arms and legs can seem to be hanging at different lengths.

In addition, you might also notice changes to gait such as arms being held tightly to the sides during motion. Balance issues can also emerge as the asymmetry caused by the scoliosis shifts a body’s center of gravity.

While only having one or two of these signs might not result in a scoliosis diagnosis, it is indicative of a need for further testing to ensure that scoliosis is not a factor.

If you have noticed some of the aforementioned signs in your adolescent, what should you do next? Basically, you are currently in the screening stage. You are looking for, and have found, some possible signs of scoliosis.

Fortunately, there is a handy and effective screening test you can do yourself from home that can give you further answers, and it’s known as the ‘Adam’s forward bend test’.

Adam’s Forward Bend Test

The Adam’s forward bend test is the go-to for school nurses and basically anyone wanting a clearer way to inspect the spine and detect whether someone has indicators for scoliosis.

To do the Adam’s forward bend,have the patient stand straight in front with their arms at their sides. Next, have them bend forward at the waist in a 90-degree angle with arms hanging down in front. In this position, the bones of the spine (vertebrae) are highly visible.

While the patient is in this position, the alignment of the spine is much easier to assess, and if the spine deviates from a natural alignment, it’s far more detectable.

In addition, as structural scoliosis has to include a curvature of a certain size and also include rotation, the torso commonly reveals the presence of scoliosis in the form of a rib arch: also far more visible in this position. This is particularly common in thoracic (middle back) curvatures as the abnormal curvature pulls at the rib cage.

Monitoring spinal curvatures is crucial for early detection and treatment of scoliosis. Smaller curvatures may remain stable, but larger curvatures can progress and lead to complications such as back pain and pulmonary dysfunction.

For even more specific and accurate screening results, the Adam’s test can be paired with an instrument called a ‘Scoliometer’.

Scoliometer

A Scoliometer is an instrument that measures trunk asymmetry and looks like a combination between a small ruler and a level. There is a notched out section that is placed over the spine, and as the instrument is pulled up and down the spine, the bubble will align with the angle of trunk rotation (ATR) that it detects.

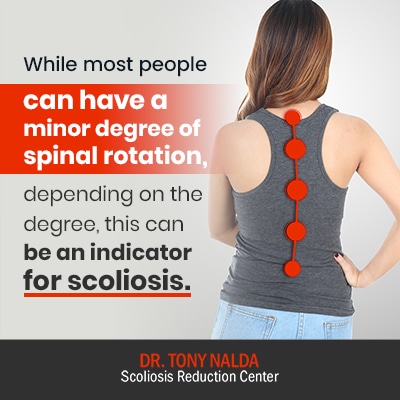

While most people can have a minor degree of spinal rotation, depending on the degree, this can be an indicator for scoliosis.

There are even apps that can be purchased to turn a mobile device into a Scoliometer.

Now, if a patient was to come into my office with concerns that they might have scoliosis, or more commonly, parents and/or caregivers bring their child in with concerns, after conducting an examination and finding indicators for scoliosis, I would take the next step of ordering a scoliosis X-ray to measure the patient’s Cobb angle.

The Scoliosis X-Ray

When a patient is first diagnosed with scoliosis, part of that diagnosis involves further classifying the condition based on a number of patient and condition characteristics: age, cause (if known), severity, and curvature location.

With the exception of patient age and cause, the above characteristics are determined by the results of the patient’s scoliosis X-ray. The X-ray helps in assessing the spinal curve, which is crucial for determining the appropriate treatment, especially when considering surgical options for severe cases.

A scoliosis X-ray can tell me everything I need to know about a patient’s condition in order to design an effective and customized treatment plan.

I can also tell a lot by the way a patient walks. When I am first examining a patient for indicators of scoliosis, observing how they talk and conducting an Adam’s test tells me whether or not an X-ray is needed.

Cobb Angle

Often referred to as the ‘orthopedic gold standard’ for assessing scoliosis, Cobb angle is measured by the most-tilted vertebrae in each curvature. Lines are drawn from the tops and bottoms of these vertebrae, and the intersecting lines form a resulting angle, and this angle is measured in degrees.

Cobb angle is the current standard for assessing how much a scoliotic spine deviates from a natural and healthy alignment.

Once a patient’s Cobb angle is determined, the condition can be further classified on its severity scale of mild, moderate, or severe.

Mild scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 10 and 25 degrees.

Moderate scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of between 25 and 40 degrees.

Severe scoliosis: Cobb angle measurement of 40+ degrees.

Once a patient’s condition is classified on its severity scale, we know how large their curvature is, and we also know some likely symptoms they might experience. I say ‘likely’ because even within each severity level, there is a huge range in symptoms and how one person experiences their condition is going to be different from the next.

As we touched on earlier, one of the big challenges of treating AIS is trying to predict progression. In some, it can be fast and seem to happen overnight; in others, it can move at a glacial pace.

While the Adam’s forward bend test/Scoliometer and measuring a patient’s Cobb angle are the more common scoliosis-assessment methods, there is another less common method that can help us gauge just how much growth a patient has yet to go through: the Risser-Ferguson Method.

Risser-Ferguson Method

As growth is the biggest trigger for progression, if we can determine how much growth is coming for a patient, we can more accurately predict their rate of progression, which is valuable information when it comes to designing a customized treatment plan.

The Risser-Ferguson method involves assigning stages from 0 to 5 to the process of ossification of sections of the pelvis. ‘Ossification’ is the process of bone-tissue formation.

The higher the stage, the closer the patient is to reaching skeletal maturity, meaning they have less growth to go through; whereas someone in a lower stage is farther away from reaching skeletal maturity and has more growth to go through.

The goal of the Risser-Ferguson method is to gauge a patient’s level of skeletal development as this information can help predict progression and impact the treatment plan moving forward.

Assessment and Treatment Approach

Now, we have talked about the nature of scoliosis as a progressive condition. We have explored the common forms in both adolescents and adults, and we have discussed common indicators of the condition for parents and caregivers to watch out for.

We have also talked about screening and assessing scoliosis via observation, the Adam’s forward bend test, the Scoliometer, the scoliosis X-ray and Cobb angle, and last but not least, the Risser-Ferguson method. Screening for scoliosis is crucial in early detection and assessment, especially in school-based programs that help identify potential spinal deformities early on.

Now that we have a good understanding of why screening and early diagnosis is beneficial and the different methods for getting there, let’s consider what happens as a condition is assessed and treatment approach is decided upon.

While the industry standard for assessing scoliosis is fairly consistent across the board: scoliosis X-ray, Cobb angle measurement, and the Risser Ferguson method, what happens next? How is the treatment approach decided, and just how much of a difference do the different approaches make to treatment outcome?

These are important questions to ask. Once you receive a scoliosis diagnosis for yourself or a loved one, while you might be recommended to take a certain treatment approach, the decision is ultimately yours.

Patients and their families should always be in charge and feel in control of their chosen course of treatment. In the context of scoliosis, there are two main treatment approaches to decide between, and this decision could make the difference between addressing the condition proactively and noninvasively, or simply observing the condition and ending up on an operating table.

The two main scoliosis treatment approaches to decide between are the traditional approach and the functional approach.

Traditional Approach

As scoliosis is a progressive condition, it’s always changing, and this necessitates a lot of monitoring and assessing the condition regularly throughout treatment to see how the spine is responding.

For those who choose the traditional path, this approach is characterized by observation. When a condition is first diagnosed, and if it’s diagnosed as a mild form, the traditional approach recommends watching and waiting. The idea is to see if, and how much, the patient’s condition is going to progress before engaging in active treatment.

It is crucial to monitor spinal curvatures to determine the appropriate treatment approach, as smaller curvatures may remain stable while larger ones tend to progress and can lead to significant health issues.

What can happen though is in between these scheduled assessment sessions during the watching and waiting, an adolescent can have a huge growth spurt that moves them into a higher severity stage.

Once this happens, the curvature is that much harder to treat because it has gotten larger. If a curvature enters into the surgical-level threshold (40+ degrees) and progression shows no sign of slowing, the patient is often funneled towards spinal-fusion surgery.

But what would have happened had active treatment been started at the time of diagnosis before the condition had progressed? What could have happened is the mild curvature could have been reduced to even smaller early on. This would mean treating a less-complex curvature while it’s small, more flexible, and easier to manipulate (curvatures get more rigid as they progress).

The hardships associated with the higher levels of progression, not to mention all the risks and potential complications of a procedure as invasive as spinal-fusion surgery, could have been avoided.

For those who come in to see me at the Scoliosis Reduction Center®, they get the benefits of a proactive alternative approach to scoliosis treatment, known as the ‘functional approach’.

Functional Approach

Here at the Center, our assessment and treatment approach differs in the end goal. We don’t want to passively observe a patient’s condition; we want to proactively treat it.

We want to help our patients avoid the hardships of ever reaching the higher stages of progression. Assessing the spinal curve is crucial in developing an effective treatment plan, as it helps determine the severity of the condition and the appropriate interventions.

We don’t want them to face the more severe symptoms of postural changes, pain, tiredness, and potential complications that can accompany progression, and we most certainly don’t want them to face spinal-fusion surgery if other less-invasive options haven’t been tried first.

By integrating multiple scoliosis-specific treatment disciplines such as targeted chiropractic adjustments, therapy, rehabilitation, and corrective 3D bracing, we can fully customize each and every treatment plan so they address characteristics of the patient and their condition.

We apportion these disciplines accordingly, and with monitoring and regular assessments performed throughout treatment, we observe how the spine is responding; the big difference in our approach is how we respond.

We are constantly modifying our treatment plans as the condition changes. If treatment is working and the curvature is reduced, related symptoms are also lessened/eliminated as the spine’s healthy curves are restored.

If we see that our plan is not staying ahead of a patient’s progressive rate, we increase treatment intensity and adjust the plan to produce different results.

We work closely with our patients and their families so they are included and engaged in their treatment plan. I find this is another benefit of starting active treatment as early as possible, rather than passively observing as in the traditional approach: patients feel more involved, more in control, and this helps lessen the feelings of powerlessness that people with progressive conditions often struggle with.

From screening to diagnosis, assessment and treatment, scoliosis is a complex condition that can develop in any age group and affect the body in a number of ways.

If you or someone you love has recently been diagnosed with scoliosis, the single best thing you can do is empower yourself with information. Fortunately, there are more treatment options available than ever before, and spinal-fusion surgery isn’t the only recourse for people.

There is an alternative, less invasive, and more natural functional approach that carries few, if any, side effects, and can offer impressive corrective results without the potential risks and complications of surgery.

Conclusion

While some states might still offer scoliosis screening in schools, the main onus falls on the parents and/or caregivers to look for the early telltale signs of scoliosis.

In adults, pain is generally the big signifier that a spinal condition is present, but as discussed, in the condition’s most common form (AIS), this isn’t the case.

The fact that AIS is rarely painful, doesn’t commonly produce functional deficits, and related postural changes can range from subtle to overt, can make it very challenging to spot the early signs.

In terms of screening, knowing when to start looking, what signs to look for, and knowing some simple tests that you can perform can increase chances of early detection.

The Adam’s forward bend test, when combined with a Scoliometer, can be an extremely effective screening method that can be done by anyone from home.

Screening tests such as the Adam’s test can’t tell you definitively whether or not scoliosis is present, but it can show whether or not a person has indicators for the condition and if further testing should be done.

If indicators are found, the next step is to get a scoliosis X-ray done, as this will reveal if the parameters for diagnosing scoliosis are met: abnormal sideways curvature of more than 10 degrees, plus a rotational component.

Once a diagnosis is given, the way in which the condition is assessed and treated moving forward will guide the patient’s experience.

For those choosing the traditional-treatment path, the approach is characterized by observation; for those choosing the functional-treatment path, the approach is characterized by action.

The traditional approach tends to observe conditions as they progress, and other than possibly using bracing in the moderate stage, there are no active treatment efforts made until a condition passes that surgical threshold, and then surgery becomes a likely outcome.

In the functional approach we offer here at the Center, as soon as we reach a diagnosis, a treatment plan is developed and active. Our results speak for themselves as with some hard work and dedication, patients can achieve a curvature reduction and improve the health and biomechanics of their spine, without having to face the permanency and risks associated with spinal fusion.

Next Steps After Scoliosis Detection

If scoliosis is detected during a screening exam, the next step is to confirm the diagnosis through imaging tests such as X-rays or MRI scans. These tests provide a clear picture of the spine’s curvature and help determine the severity of the condition. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the child’s doctor will develop a treatment plan tailored to the individual’s needs.

The treatment plan may include observation, bracing, or surgery, depending on the severity of the curvature and the child’s age and growth potential:

- Observation: For mild cases, the doctor may recommend regular monitoring to see if the curvature worsens over time. This approach is often used for children who are still growing.

- Bracing: In moderate cases, wearing a brace can help stabilize the spine and prevent the curvature from worsening. Bracing is most effective when the child is still growing.

- Surgery: In severe cases, surgery may be necessary to correct the curvature and prevent long-term complications. Surgical options aim to straighten the spine and stabilize it using rods, screws, and bone grafts.

It’s important for parents to work closely with their child’s doctor to develop a treatment plan that meets their child’s individual needs. Ensuring that the child receives the best possible care involves regular follow-ups and adherence to the recommended treatment regimen. Early intervention and a proactive approach can significantly improve the child’s quality of life and long-term outcomes.